Training to write, the way Federer trains to win

Can writers learn from how tennis players train? I’ve seen Roger Federer train and what he does is simple exercises like hitting a forehand, hitting a backhand, overhead smashes or running around the court throwing a ball and catching it. These and more he does every day, that constant repetition ensuring that he can do it effortlessly when the time comes, so that he doesn’t have to think in the heat of the moment. A full list might look something like this:

forehand - sliced, top spin

backhand - sliced, top spin

smash

serve, to forehand, backhand and body

pass down the line

pass cross court

overhead lob

drop shot

between the legs running back

coming into the net

watching the ball onto the racket

grip

What should a writer do that is equivalent? I’m not sure. I’ve never seen any writers discuss this. Advice usually comes in the form of “Write” or “Write every day”, which is fine. But I wonder if it could be more targeted.

A draft list of techniques to practise might look something like this:

Getting to the truth of a scene

Describe a person in one sentence

Describe a natural scene, a tree or a sunset

Metaphors

Similes

Analogies

Rule of 3

Show don’t tell

Contrast

Repetition

Alliteration

Synonyms (needs extensive vocabulary)

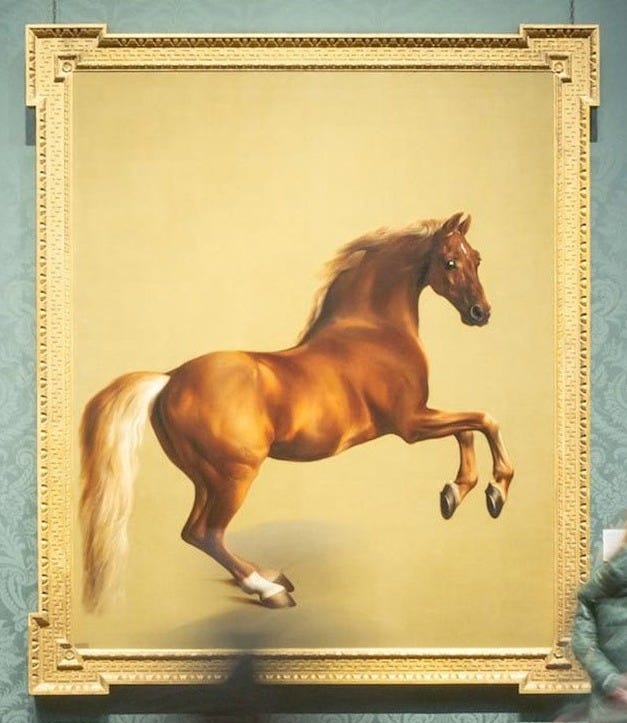

The next trick is to devise practice exercises for each. For example, one might be “pick 10 photos from the National Gallery website and describe what you see”. Start simply, then elaborate. For the below image you might say “A horse rearing on its hind legs”. I imagine if you did this regularly the technique would eventually become to seem instinctive.

If you described the same horse every day, you would start to play with it. Instead of saying “horse on its hind legs” you might start to say “chestnut beast rising up”. Or you might ignore the horse and say “square frame filled with mustard” focusing on the negative space.

Another practice exercise might be to pick a phrase and come up with synonyms for it, eg “it was a joy”. An alternative might be “it was a pleasure”. But no, it has the same cliched quality and doesn’t get across that delirious feeling of joy. If you struggle, then go to the thesaurus and write down 10 alternatives. In this act of writing them down, over time and with repetition they would start to become second nature and you will be able to produce them when needed.1

Each technique would need a practise exercise and this would form the basis for the writer’s training, their equivalent of going to the practice courts or gym.

All these are tools to be deployed when the need is there. They exist to fulfil the aim of writing: evoking emotion, arguing a point, telling a story, revealing truth or portraying what it is to be human. There isn’t one aim, but then there isn’t in tennis either. The player wants to win the game, but a Federer wants to win with style and leave the crowd dazzled by his repertoire of shots, his elegance and his power.

Above all I think what the writer needs is descriptive power. A writer should be able to sum up a person or a scene or convey an emotion, preferably in very few words, to rapidly transport the reader into another world, the way a Federer summons up an ace on break point.

I think vocabulary should be broad enough but not too broad so that the reader doesn’t understand such as words like “dithyramb”, “raddled” or “midden”, which are interesting, appealing words I’ve seen in Will Self’s writing but I had to look them up. Unless, and this would be very hard, they can be introduced in a way that explains them. If not, this type of writing alienates rather than communicates, the equivalent of the dandy wearing rings, a pocket watch, a tie clip, a hat, a waistcoat - it’s too much, too laboured, too show-offy.

Besides, there is no need to use long, exotic words to be considered great. I remember being astonished at how easy to read Tolstoy was. I had a prejudice that because he’d written the 1,500 page classic War and Peace that his writing should be difficult and unpenetrable, but it was a joy. Admittedly I was reading it in the English translation from the Russian by Louise and Aylmer Maude, so perhaps I should say I remember being astonished at how easy to read the Maudes were. They may have stripped out any pretentious or ponderous language that Tolstoy indulged in.